Sustainability and returns

The misconception that strong environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance only comes at the expense of business performance has been debunked for some time now[1]. One of the most recent studies on this subject from Morningstar tracked a portfolio of highly rated ESG companies for ten years to examine their risk/return characteristics to determine whether investors paid a premium for these stocks1. As with other studies before it, the results concluded there was no evidence that investors need to sacrifice returns to invest in good ESG companies.

Managers of companies are also aware of this concept. A commitment to sustainability has become an essential part of many organizations’ values and strategic goals[2]. Many firms have dedicated ESG employees and generate annual sustainability reports highlighting their accomplishments in corporate social responsibility. Yet there appears to be a dichotomy between many firms’ philosophies around ESG and the capital projects they undertake. In 2015, Meyer and Kiymaz surveyed executives to determine whether sustainability was a regular consideration in their capital budgeting process[3]. The results discovered that it was not a significant consideration when making capital investment decisions3. The reason for this contradiction may seem obvious to many people; firms in certain industries have inherently inferior ESG assets (ex. oil refineries), so they must find other ways to boost their corporate sustainability record. Others may point to the difficulty in quantifying the intangible ESG elements of a project, which could create capital budgeting inaccuracies that could lead decision-makers to pass on otherwise attractive investments (or accept inferior ones)[4].

But while these may sound like reasonable justifications for ignoring sustainability in project appraisal, the reality is that ESG principles are here to stay. Policies and regulations around issues such as climate change and the environment are in constant flux, and projects that seemed solid under traditional capital budgeting methods may not be so attractive after new ESG laws come into effect. Executives who recognize this should consider building sustainability elements into their capital budgeting process to ensure their company is selecting robust projects that can stand up to the increasingly intense environmental and social headwinds that organizations will face.

Traditional capital budgeting techniques

Companies use capital budgeting to help decide which long-term assets are worth pursuing4. Investments such as property, plant and equipment are analyzed to determine if they will make a positive contribution to the companies overall value. The primary techniques used for capital budgeting are discounted cash flow (DCF) methods, namely net present value (NPV) and internal rate of return (IRR)4. While other techniques such as payback period and accounting rate of return are also used, the focus of this discussion will be on DCF techniques.

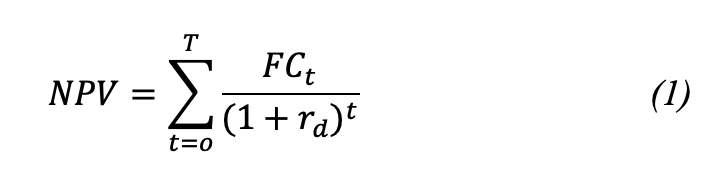

Short-life projects are often not the most valuable, and discounted cash flow methods of capital budgeting integrate the time value of money into the decision process allowing managers to compare projects that span several years into the future4. With modern technology such as spreadsheets and software, it is relatively easy to calculate all capital budgeting methods. For example, to calculate the NPV of a project, the residual annual cash flows from the project are discounted at the company’s cost of capital and summed to give the present value of the investment4. The difficulty lies in determining exactly how much cash flow a project will produce each year, estimating the cost-of-capital to discount these cash flows, determining the useful life of the asset, and integrating project risk into the cost of capital[5]. Changes in these underlying assumptions can drastically change the appeal of potential alternatives. Over time, analysts have developed standard methods for determining many of these factors, so while there is room for variations, the DCF approach to capital budgeting is relatively consistent5. Within DCF models, traditional line items affecting cash flow include taxes, depreciation and various project costs such as inventory5. If an investment has a positive NPV, the company should do the project5. The typical approach to determining NPV is illustrated in Equations 1[6].

FC is the sum of the cash flows each year over the project’s lifetime, T6. These cash flows are discounted back to the present (t=0) at a rate of rd for each year, t, of the project6. The higher the NPV, the more attractive the investment appears from a value-adding standpoint5. Companies that cannot do all the projects available to them will choose the one(s) with the highest NPV. If there are factors that affect cash flow that have not been accounted for in the model, then a company may take on the wrong project. One glaring example of factors that are commonly left out of traditional DCF techniques are what economists refer to as externalities.

Externalities

When a company or a project creates a cost or benefit that is not incurred or received by the producer, it is called an externality[7]. Externalities can affect both individuals, organizations, or society as a whole7. Many ESG related issues are considered externalities because they involved stakeholders who do not benefit from a business’s activities. Pollution is a typical example of an externality because it is generated by one organization but negatively impacts the entire region7.

Some economists believe that market failure occurs if a product’s price does not reflect all the costs associated with producing it7. Governments are cognisant of these adverse effects on society and are taking steps to push the costs of these externalities back on to the producers who create them7. Taxes equal to the value of the negative externality are one way to fight these social costs7. Another way to curb this issue is to use subsidies that encourage the consumption of positive externalities7.

When governments implement these policies, it places pressure on companies’ business models that rely heavily on negative externalities. Capital investments that used to add significant value to the firm may suddenly become a burden. To avoid this threat of evolving policy, organizations should attempt to capture as many externalities (both negative and positive) in the capital budgeting process as possible to ensure they are selecting alternatives that are sustainable in the long-term5.

Sustainability and capital budgeting

To integrate sustainability into the capital budgeting process, companies must go beyond the typical “useful-life” accounting concept and attempt to estimate the project’s cash flows from the cradle to the grave[8]. Kimbro suggests using a life cycle cost (LCC) and life cycle assessment (LCA) approach to incorporating sustainability into the cash flow prediction process8. Unlike a traditional economic analysis, LCC involves creating an extensive list of environmental and social costs and benefits relevant to the project throughout its entire life8. Kimbro provides a comprehensive list in Table 1 that can be used for this analysis8. If an item is identified as relevant, it should be quantified and explained8. LCA then attempts to assign a probability to each of these costs and benefits8.

Table 1: Initial inventory of costs and benefits (Source: M.B. Kimbro, 2013)

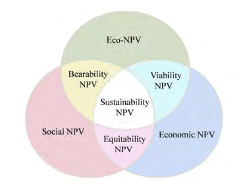

Zore et al. have taken this integration one step further with the concept of Sustainability net present value (SNPV)[9]. The mechanics of SNPV are a composite measure of economic net present value (NPVEconomic), eco net present value (NPVEco) and the social net present value (NPVSocial)9. NPVEconomic is the traditional component of capital budgeting seen in Equation 19. NPVEco represents the present value of environmental issues such as pollution and energy use and takes the same general form as Equation 1[10]:

FCEcot is based on the concept of eco-profit, which is the difference between eco-benefits (EBt) and eco-costs (ECt)10. Eco-benefits are the cash flows that occur in year t from avoiding environmental damage and availing of subsidies, while eco-costs are the cash flows that are required in year t to avoid environmental burdening10. Thus, FCEcot in year t can be defined as:

Each alternative will have unique EBt and ECt that must be broken down according to the specific technologies, energy usage, raw materials, and waste generated by that project10. Once expression 3 has been refined, it can be inserted into Equation 2.

NPVSocial consists of the present value of the project’s support for employees and the local community10. Equation 4 defines the social net present value as:

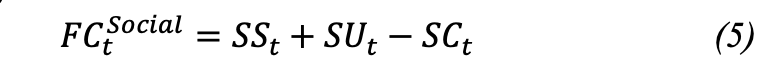

Zore et al. express FCSocialt at year t as:

SSt represents the social contribution of the project, SUt denotes the social unburdening effect of job creation, and SCt stands for social cost10. Depending on the company’s approach to social impact, these variables may be described differently. Zore et al. have taken a government-industry view of social contribution, integrating the effects on the state into FCSocialt. As this is somewhat subjective, organizations may choose to define social contributions and social costs in other ways. Once this has been determined, Equation 5 can be substituted in Equation 4 to determine the NPVSocial.

Combining these three elements, we can define sustainability net present value as10:

The final piece of integrating sustainability into the capital budgeting process is through the cost of capital. Traditionally, this rate is determined from the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) in conjunction with the project’s risk level[11]. One way to develop a “Sustainability Risk Rate” is to run each alternative through an environmental and social risk inventory checklist11. The company must use these environmental and social filters to determine a risk rate that can be added to the WACC for each project11.

Assessment of sustainable capital budgeting

The Life-Cycle approach is a good starting point for any organization seeking to integrate sustainability into its capital allocation process. However, the LCC and LCA frameworks are too vague when used in isolation, and should be used as the first step to identify relevant inputs for the SNPV model and the sustainability risk rate.

One of the main benefits of separating economic, environmental and social factors in the SNPV model is its flexibility. Zore et al. demonstrate this flexibility by assigning weights wa, wb, and wc ranging between 0 and 1 to each component of the SNPV equation[12]:

These weights allow decision-makers to prioritize the parts of the capital budgeting process that matter most to their stakeholders. From Equation 6 we know that weights of 1 for each composite NPV will yield Sustainability net present value12. Zore et al. have also defined several other combinations of weights that prioritize different factors (Table 2)12.

Table 2: Coefficients for various NPVs (Source: Zore et al., 2018)

Another benefit of the SNPV approach is its capacity to integrate a group of projects to achieve the optimal mix of alternatives. Certain companies have to choose a combination of capital projects that deliver the best return for their stakeholders. For example, a utility company may have to select alternatives from a wind farm, a coal-fired plant, a natural gas turbine, photovoltaic arrays and hydro generation12. No one project can meet demand on its own, so the utility will have to invest a combination of these alternatives12. This decision could be viewed as a supply network problem, with the goal of maximizing Equation 7, the objective function, subject to various constraints (ex. forecasted demand, operational, environmental)12. With the aid of linear programming software, the utility could list as many constraints as necessary12. The decision-maker can then manipulate the weights of each composite NPV to determine the best combination of projects for the company12.

Recommendations

Balance short-term success with long-term sustainability

The concept of SNVP is important for all industries, and it is most relevant for companies that are presented with the choice between low ESG and high ESG alternatives, such as the utility example discussed above. The traditional DCF analysis does not consider these factors, leaving companies vulnerable to the changing macro-environment. With government policies focusing on factors such as climate change mitigation, capital assets could be impaired by new regulations. In the best-case scenario, this could mean an underperforming asset, while in the worst-case, companies could be left with stranded assets.

Nevertheless, companies have many stakeholders with a short-term focus applying pressure on decision-makers to choose projects that will deliver an attractive return in the near future[13]. This myopic view is generally considered a poor way to run a company, but this report recognizes that a balance may need to be struck between short-run success and long-term sustainability. Therefore, it is recommended that decision-makers examine the various potential future environments their organization will face using scenario analysis. Different scenarios will present different costs and benefits, which will, in turn, affect the SNPV of an alternative. Running variables from different scenarios through the model may delineate certain hidden risks associated with the project. The scenario with the highest probability of becoming a reality should ultimately be used for inputs into the final capital budgeting analysis. Depending on which outcome seems most likely to occur, more weight may be assigned to one composite NPV over another. For example, if the probable scenario is one where environmental regulations are relatively lax, a company may find that assigning more weight to NPVEconomic in Equation 7 maximizes the total return of the project.

There are no rules set in stone for this capital budgeting process. Each company will be faced with a different set of outcomes, costs, benefits, and projects based on its industry and macro-environment. But if decision-makers are diligent in their scenario planning and create detailed SNPV models that consider the project’s entire life-cycle, companies will find their investments have long-term sustainability and stable returns.

Conclusion

As we move into the future, more of these social and environmental factors will become required by law. Traditional capital budgeting techniques may leave organizations exposed to these ESG related risks. Projects that already have these environmental and social factors incorporated in their financial structure will be more resilient to regulatory and societal headwinds. Using the life-cycle assessment combined with the SNPV model provides firms with a more robust approach to capital allocation. Scenario planning can help decision-makers determine the weight to be applied to each section of the SNPV model to appease all stakeholders and ensure the long-term sustainability of the organization.

[1] Wang, P. & Sargis, M. (2020, February 20). Better minus worse. Evaluating ESG effects on risk and return. Morningstar.

[2] Sexty, R. (2017). Canadian business and society: Ethics, responsibilities, and sustainability, 4th edition. McGraw-Hill Ryerson.

[3] Meyer, K. S. & Kiymaz, H. (2015, February 25). Sustainability considerations in capital budgeting decisions: A survey of financial executives. Sciedu Press: Accounting and Finance Research.

[4] Kimbro, M. B. (2013). Integrating sustainability in capital budgeting decisions. In P. Taticchi et al. Corporate sustainability, CSR, sustainability, ethics & governance (pp. 103-114). Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

[5] Kimbro, M. B. (2013). Integrating sustainability in capital budgeting decisions. In P. Taticchi et al. Corporate sustainability, CSR, sustainability, ethics & governance (pp. 103-114). Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

[6] Zore, Z. Cucek, L., Sirovnik, D., Pintaric, Z. N & Kravanja, Z. (2018, January 1). Maximizing the sustainability net present value of renewable energy supply networks. Chemical Engineering Research and Design.

[7] Kenton, W. (2020, May 29). Externality. Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/e/externality.asp

[8] Kimbro, M. B. (2013). Integrating sustainability in capital budgeting decisions. In P. Taticchi et al. Corporate sustainability, CSR, sustainability, ethics & governance (pp. 103-114). Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

[9] Zore, Z. Cucek, L., Sirovnik, D., Pintaric, Z. N & Kravanja, Z. (2018, January 1). Maximizing the sustainability net present value of renewable energy supply networks. Chemical Engineering Research and Design.

[10] Zore, Z. Cucek, L., Sirovnik, D., Pintaric, Z. N & Kravanja, Z. (2018, January 1). Maximizing the sustainability net present value of renewable energy supply networks. Chemical Engineering Research and Design.

[11] Kimbro, M. B. (2013). Integrating sustainability in capital budgeting decisions. In P. Taticchi et al. Corporate sustainability, CSR, sustainability, ethics & governance (pp. 103-114). Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

[12] Zore, Z. Cucek, L., Sirovnik, D., Pintaric, Z. N & Kravanja, Z. (2018, January 1). Maximizing the sustainability net present value of renewable energy supply networks. Chemical Engineering Research and Design.

[13] Sexty, R. (2017). Canadian business and society: Ethics, responsibilities, and sustainability, 4th edition. McGraw-Hill Ryerson.