An article I wrote for a data management course summarizing some potential applications of blockchain in the public sector, health care and education. Thought it would be relevant to post in light of the breakout year crypto is having. Some concepts already seem a bit naive to me since my knowledge on the subject has grown. Nevertheless, some of the points are still interesting to me and probably deserve closer attention.

There has been enormous media coverage recently of blockchain and the cryptocurrency world that has been built on top of this technology. Many pundits believe blockchain is the most revolutionary invention since the internet was first developed. Its distributed characteristics promise to reduce society’s reliance on intermediaries and decentralize power in many ways. Futurists can often be heard on podcasts and YouTube discussing a world without banks, lawyers, insurance companies, and even fiat currency. Consultants are telling businesses and public institutions that early adopters will have a strategic advantage over laggards.

However, despite the media coverage and blockchain’s pervasiveness in online culture, the technology’s potential remains largely untapped for enterprise-scale applications.

Today, many organizations are undergoing a broad digital transformation as they become inundated with data and new technology to manage said data (Furlonger & Uzureau, 2019). It can be difficult for leaders of large incumbent institutions to know which technologies to pursue to add real value to their organization. Financial institutions have been some of the earliest adopters due to the rise of cryptocurrency (Nofer et al., 2017). However, perhaps some of the technology’s greatest potential lies within the field of data management (Yumna et al., 2019).

The following report aims to delineate blockchain’s potential uses in the data management space by highlighting its competitive characteristics and discussing existing examples of how it is already being used today.

How blockchain works

While blockchain’s roots can be traced back several decades, the technology gained prominence in 2008 when it was used as the underlying mechanism for Bitcoin, a cryptocurrency (Nakamoto, 2008). While the Nakamoto paper does not explicitly name the technology, it described in essence what we know today as blockchain. The paper described a peer-to-peer network for electronic transactions that uses a concept known as proof-of-work to create a public record that becomes computationally unfeasible to change (Nakamoto, 2008). Furlonger and Uzureau (2019) provide us with a more refined definition of blockchain: “a digital means to create a distributed ledger where two or more participants in a peer-to-peer network can exchange information and assets directly without the need for a trusted intermediary.”

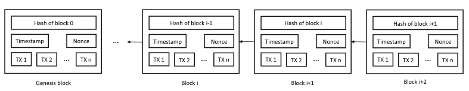

The basic mechanics of a blockchain are illustrated in Figure 1. The chain is comprised of data packages or blocks (Nofer et al., 2017). Each package is subsequently made up of multiple transactions (TX 1-n) along with the hash value of the previous block, a time-stamp and a number used to verify the hash, called a nonce (Nofer et al., 2017). Transactions occur through a public-private key system that maintains the anonymity of the buyer and the seller (Nakamoto, 2008). Each block in the network is validated through a cryptographic techniques. In the Nakamoto paper, the technique used is proof-of-work, which requires finding a hash value with a specific number of zero bits (Nakamoto, 2008). The block cannot be changed once the proof-of-work has been satisfied (Nakamoto, 2008).

Figure 1: Example of a blockchain (Zheng et al., 2017)

This technique also creates a majority consensus mechanism to validate the block and the transactions it contains. Satisfying the proof-of-work requires CPU power, and the longest chain, which has invested the greatest amount of CPU effort, represents the majority decision-maker (Nakamoto, 2008). When the majority of nodes on the network agree via the consensus mechanism, the block can be added to the chain (Nofer et al., 2017). The Nakamoto paper goes on to demonstrate that the probability of an attacker surpassing the honest chain becomes exponentially smaller as more blocks are added. Several blockchain groups have developed other consensus algorithms since bitcoin was first created (ex. proof-of-stake), but proof-of-work continues to be the dominant mechanism used today (Zheng et al., 2018).

The difference between blockchain and relational databases

A common misconception is that blockchain is a type of database. A business leader new to the technology may read this and wonder why they would focus on such an application when existing database options already meet the organization’s needs. However, blockchain technology is not a database, at least in the traditional sense. Today’s relational databases are centralized in nature, with an administrator overseeing all aspects of the system (access, privacy, security). This configuration is known as a client-server architecture. Blockchain, on the other hand, has a distributed architecture that does not require an overseer. This difference makes relational databases susceptible to malicious attacks, while blockchain is relatively impregnable. An attacker would have to redo the proof-of-work and then surpass it to gain control of the network, a probabilistically minuscule feat (Nakamoto, 2008). The distributed nature of blockchain also improves transparency over relational databases because all nodes on the network have a copy of the leger (Furlonger & Uzureau, 2019). The data integrity of a blockchain is, therefore, much better than traditional forms of data management. One caveat to this is that data on a blockchain cannot be changed, whereas relational databases have create, read, update and delete capabilities. This feature may be desirable for some forms of data while impractical for others.

The Gartner Institute summarizes the features of blockchain technology into five core elements that create a novel architecture that can provide some advantages over traditional methods of data management (Furlonger & Uzureau, 2019).

| Distribution – Nodes, or machines, participating in the blockchain are physically distributed, each with their own complete copy of the leger. This feature improves transparency as anyone can review (but not alter) the information. |

| Encryption – While distribution enhances transparency, the public and private keys used in blockchain technology improve privacy by providing participants with pseudonyms (Nakamoto, 2008). This element allows blockchain members to share only what they need to complete a transaction. |

| Immutability – Due to the cryptographic techniques describe above, transactions added to the leger cannot be manipulated in any way. |

| Tokenization – The exchange of valuable information on a blockchain comes in the form of a token. These tokens can represent many different ideas, including physical assets or incentives for market participation. Many distributed applications are built using tokens as a medium of exchange (Furlonger & Uzureau, 2019). Within the realm of data management, they can provide individuals and corporate participants with more control over their own data. |

| Decentralization – As described before, blockchain creates a consensus mechanism that removes the need for a central authority. As the network is maintained by multiple nodes, no single individual or organization can dictate the rules for how the blockchain is managed (Furlonger & Uzureau, 2019). |

When combined, these features create a system that can provide improved transparency, better security and privacy, while eliminating the need for an intermediary or administrator. From an organization’s perspective, this type of network may not be optimal for every data type. However, the automation blockchain provides can lead to business process efficiencies and costs savings when used appropriately (Niranjanamurthy et al., 2019). Based on the dichotomous nature of these two data management systems, this report expects blockchain and incumbent technologies to exist in parallel at the organizational level in the future, with the former replacing some (but not all) forms of legacy systems. The following section builds on this idea by presenting ways in which blockchain can improve the management of certain data types.

Blockchain applications in data management

Experts have identified many opportunities to improve data management using blockchain technology. Niranjanamurthy et al. (2019) conducted a SWOT analysis to highlight the pros and cons of potential adoption. The strengths mentioned in the previous sections can lead to opportunities involving automation, the elimination of intermediaries, improved customer experience, reduced costs, and many prospects within the Internet of Things (Niranjanamurthy et al., 2019). There are already examples of blockchain improving organizations’ data capabilities in almost every sector (Furlonger & Uzureau, 2019). Three areas of particular interest are the public sector, health care, and education. These institutions are pillars of our society but suffer from sluggishness due to their size and organizational structure. It is in areas such as this where the strengths of blockchain technology can have a significant impact.

Public Sector

Governments collect a vast amount of data on the people, assets, and organizations they preside over. Tax information, social insurance numbers, real estate ownership and incorporation filings are just a few examples of the sensitive data governments manage (Cheng et al., 2017). These documents are kept in a centralized system, usually a relational database, although many documents may exist in paper form. The bureaucratic, slow-moving nature of public institutions can make accessing this information cumbersome and inefficient. Furthermore, the centralized nature of this information makes it vulnerable to cybersecurity attacks. Blockchain has the potential to change this.

Protecting critical data is a primary concern for governments because a breach could damage the people’s trust in the institution. Despite best efforts, incidents do occur, such as the 2015 attack on the US government when the social security numbers of roughly 20 million Americans were compromised (Cheng et al., 2017). This attack could have been prevented if this data had been stored on a blockchain.

Estonia’s government has already implemented blockchain technology to protect its public data (Cheng et al., 2017). The Estonian government takes large amounts of public data and represents it with a hash value, which is subsequently stored on a blockchain (Cheng et al., 2017). These hash values can only be used to access the records but not recreate any information (Cheng et al., 2017).

Digital property ownership is another example of how blockchain can improve government record keeping. Anyone who has purchased a home (particularly an old property) knows how onerous the paper trail of title searches can be. The government of Sweden is experimenting with blockchain to digitize this time-consuming process (Cheng et al., 2017). The country’s land-registry authority is piloting a mobile app that will record all real-estate transaction information on a blockchain, making it faster and more transparent for all parties involved (Cheng et al., 2017). Buyers, sellers, real estate agents and lenders would have access to the same up-to-date information in real-time. This system has the potential to improve the property transfer process and reduce closing times drastically. McKinsey, a management consulting firm, estimates that buyers in OECD countries pay $3.5 billion per year in real estate transaction fees (Cheng et al., 2017). Moving land registration to a blockchain could significantly reduce governments’ costs, and these savings could be passed on to buyers (Cheng et al., 2017).

Another example of how the public sector is using blockchain is through the use of smart incorporations. The process for incorporating a business involves a multitude of paperwork and filings. The US state of Delaware is looking at digitizing the incorporation process through the use of blockchain technology (Cheng et al., 2017). The ownership structure could be defined through the use of smart contracts (Cheng et al., 2017). A smart contract is a program embedded on the blockchain and can be used to define rules similar to a real contract (Richards, 2021). As company equity structures become increasingly complicated, this system will add more value by saving government institutions time and money.

Education

Education is proving to be another area where blockchain can have a significant impact. Schools deal with many of the same issues that governments and health care face. Educational institutions collect sensitive information on students, which requires private and secure management. As this report has already demonstrated, blockchain provides solutions to these issues. However, schools have unique problems that can also be addressed using this distributed technology.

Yumna et al. (2019) conducted a systematic literature review to determine areas in the field of education that could be improved through the use of blockchain technology. From their review, educational institutions’ issues included manipulation risk, verifiability, transferability, and demand on human resources (Yumna et al., 2019).

Manipulation of educational documents, including falsifying grades and diplomas, has been a real problem for post-secondary institutions in recent years (Szeto & Vellani, 2017). Manipulation risk exists primarily because of human involvement in creating educational records (Yumna et al., 2019). This risk is compounded by the fact that schools find it difficult to verify students’ and facultys’ credentials due to problematic record-keeping at other institutions (Yumna et al., 2019). This problem is particularly true in developing nations where data management systems are not as refined (Yumna et al., 2019). A solution to this lies in the immutable and transparent nature of blockchain technology. If academic institutions issued credentials on a blockchain, they would be both tamper-proof and easily verifiable by other institutions. In Australia, the University of Melbourne became one of the first educational institutions to issue credentials on a blockchain using an app for mobile devices (University of Melbourne, 2017).

Blockchain credentials can also improve the exchange of records between institutions (Yumna et al., 2019). Transferring credits or partial degrees from one institution to another can be difficult and is sometimes impossible because no global standard exists (Yumna et al., 2019). Similar to immutable credentials, course information and student records could be included on the distributed ledger to simplify the transfer process.

Finally, the distributed element of blockchain reduces the demands on human resources. With a distributed ledger, all parties would be privy to the most updated version of an individual’s academic record, eliminating many hours of labour required from a school’s registrar’s office.

Health Care

Trust is a cornerstone of any health care system. Whether it is a public system such as in Canada or a private model like the United States, citizens rely on our health care institutions to provide effective services. One of the significant roadblocks to efficiency within our health care network is the lack of interoperability between different enterprises (Krawiec et al., 2016). Deloitte, a management consulting firm, proposes a new model for Health Information Exchanges (HIEs) using blockchain technology (Krawiec et al., 2016).

HIEs allow for the exchange of data between different stakeholders (doctors, nurses, pharmacists and patients) within a health care network (Kuperman, 2011). However, these systems have many pain points, such as a lack of trust and transparency, high cost per transaction, varying standards around data, and different rules regarding access (Krawiec et al., 2016). These are natural outcomes when information is kept in centralized systems siloed from each other. Moving health care data to a blockchain addresses many of these issues.

One of the fundamental features of blockchain is it removes the need for a trusted central entity because all participants can view the leger. The Deloitte paper points out that this feature would lead to disintermediation where an HIE administrator would not be required (Krawiec et al., 2016). This disintermediation, along with blockchain’s real-time processing, would, in turn, lead to reduced transaction costs (Krawiec et al., 2016). Furthermore, shared data on the chain eliminates problems with data standards and instead provides immediate updates for all network participants (Krawiec et al., 2016). Finally, smart contracts can be employed to create rules and permissions for accessing patient data (Krawiec et al., 2016).

An HIE based on blockchain technology would improve data integrity in health care systems, providing patients with greater visibility of their data while maintaining anonymity. Figure 2 illustrates how the complete system would function.

Figure 2: Proposed HIE model using blockchain. Adapted from Krawiec et al., 2016.

This model could be used to manage sensitive information in other industries, including the examples from government and education mentioned above.

Challenges to implementation

While the blockchain applications mentioned in the previous section present an opportunity for real impact in their respective sectors, there are several challenges when it comes to implementation. The SWOT analysis from Niranjanamurthy et al. (2019) identified several weaknesses that will create headwinds for blockchain adoption. Several of these issues are technical in nature, while others are administrative. Two of the primary technical problems are scalability and privacy leakage (Zheng et al., 2018)

Scalability

One of the main issues blockchain faces is scalability. As previously mentioned, each node in the network must validate a new transaction before it can be added to the chain (Chauhan et al., 2018). All transactions are stored on the blockchain, making it longer and “heavier” over time (Zheng et al., 2018). Due to the proof-of-work consensus method and the limited size of each block, an increase in transactions leads to a decrease in scalability (Chauhan et al., 2018). As more transactions occur, more nodes are required to support the network (Chauhan et al., 2018). However, this concurrently increases the distance each transaction must travel to satisfy to be validated (Chauhan et al., 2018). This flaw in the technology creates a significant barrier to adoption at an enterprise scale because large organizations tend to have high volumes of transactions. Currently, the Bitcoin blockchain can handle approximately four transactions per second (Blockchain, 2021). This number is minuscule when compared with Visa’s 1670 transactions per second (Chauhan et al., 2018).

Privacy Leakage

Despite Nakamoto’s (2008) work demonstrating the blockchain’s privacy and security, cybersecurity concerns still exist. The blockchain cannot guarantee privacy since all participants’ public keys are available to everyone (Zheng et al., 2018). Biryukov et al. (2014) illustrated a method to link public keys to IP addresses even when the member is using a firewall.

Culture

There may also be large cultural barriers to adoption at an enterprise scale. Many new technologies do not represent a drastic departure from the way we currently work. Instead, most technological advances provide incremental efficiency improvements and are easily absorbed into our regular lives. On the other hand, blockchain is a radical shift from how certain types of information are managed and will require significant change management. Moving to trust a trustless network may take more time to achieve a critical mass buy-in than less transformational technology.

Figure 3: Blockchain spectrum (Furlonger and Uzureau, 2019)

Conclusion

Not all data management issues can be improved through blockchain. Leaders will need to examine each situation within their organization and decide whether this new technology is appropriate. Blockchain will most likely replace some incumbent technology but will coexist alongside other legacy systems.

When it comes to data privacy, organizations should consider blockchain as a viable option for storing information. While no encryption method can ever be 100 percent foolproof, this technology could prevent many of the breaches that occur today (Cheng et al., 2017). This technology is still in its early days. As Figure 3 from the Gartner report illustrates, we are just at the cusp of seeing complete blockchain applications come to fruition (Furlonger & Uzureau, 2019). It is almost guaranteed that blockchain technology will play an important role in the future of data management. As pointed out previously, widespread adoption within an organization’s culture will take time. Companies and institutions who begin that process now by researching and developing ways to apply blockchain will be well-positioned to manage data more efficiently in the coming decade.